By Patience Gondo

Zimbabwe’s return to single digit inflation is being celebrated as a historic breakthrough and rightly so.

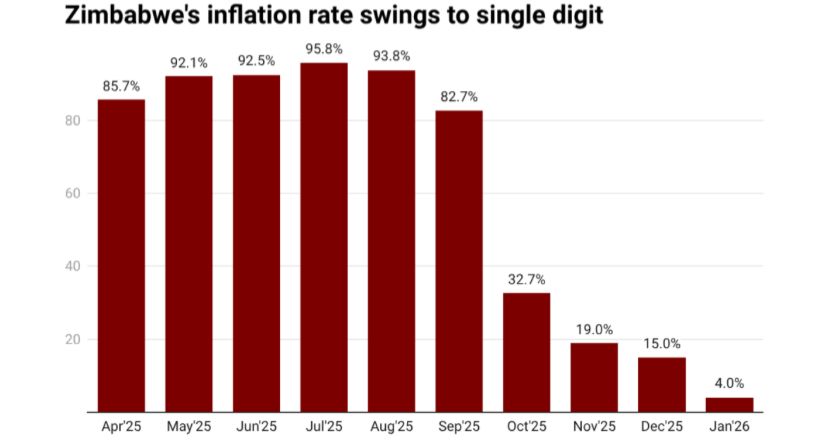

After nearly three decades of persistent price instability, official figures show annual inflation falling below 10 percent for the first time since 1997.

In January 2026, year on year ZiG inflation stood at 4.1 percent, while month on month inflation was recorded at zero percent.

The Government attributes this outcome to deliberate policy action.

In a statement on Monday Finance, Economic Development and Investment Promotion Minister Professor Mthuli Ncube said the decline in inflation was a result of concerted and consistent efforts by the Ministry of Finance, Economic Development and Investment Promotion and the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe through the implementation of complementary fiscal and monetary policies.

But while the milestone is real, it requires careful interpretation.

Single digit inflation does not mean prices become cheaper.

It means prices are no longer rising rapidly.

The distinction is critical and it is where economic statistics often collide with lived reality.

Inflation, by definition measures the rate of price increases, not the actual price level.

When inflation falls, it does not undo previous price hikes. It merely slows or halts further increases.

In Zimbabwe’s case, prices rose sharply over many years before stabilising. That elevated base remains intact.

A simple example illustrates this reality. If a 10kg bag of mealie meal doubled in price during periods of high inflation, a drop in inflation does not halve the price again.

The bag stays expensive; it just stops becoming more expensive every month.

Stability preserves prices it does not erase them.

The January data, particularly the zero percent month on month inflation, suggests that price pressures have temporarily eased.

This aligns with the Government’s position that tighter liquidity management and policy coordination have reduced inflationary momentum.

According to Professor Ncube, price stability carries broader economic benefits.

“For citizens, stable prices preserve the purchasing power of income and protect savings. For business, it enables long term planning, reduces operational costs and enhances profitability,” he said.

Stable prices are a prerequisite for confidence, investment and planning.

However, economic stability and affordability are not the same thing.

Most households earn incomes that adjusted slowly, if at all, during years of high inflation. Wages, pensions and informal earnings lagged behind rising prices, leaving families with diminished purchasing power.

Slower inflation does not immediately restore that lost ground.

This explains why many citizens may not feel the statistical success.

Market prices are no longer jumping weekly, but they remain out of reach for households whose incomes have not caught up.

Economists describe this as an inflation income gap a phase where price stability returns before prosperity does.

Importantly, this reality does not diminish the significance of the achievement. Low and stable inflation is a necessary foundation for economic recovery.

Without it, planning becomes impossible for businesses, savings are eroded and long term investment evaporates.

What the current figures show is that Zimbabwe has entered a phase of price stability, not price relief.

The danger lies in overselling the moment. History shows that premature celebration often precedes policy slippage.

Inflation control must be sustained through fiscal discipline, restrained public spending and credible monetary management. One month of calm does not guarantee a peaceful year.

For now, single digit inflation should be understood for what it truly is , a pause in the storm, not the clearing of the skies.

Prices are no longer rising fast and that matters. But cheaper living will only come when incomes rise, productivity improves and stability endures.